Chikaire, J.U

Department of Agricultural Extension, Federal University of Technology, Owerri, Imo State, Nigeria

Atoma, C.N

Department of Agricultural Extension and Management, Delta State Polytechnic, Ozoro, Delta State, Nigeria

Ajaero, J.O

Department of Agricultural Extension, Federal University of Technology, Owerri, Imo State, Nigeria

*Corresponding author: Chikaire, J.U, Email: futoedu23@gmail.com

Abstract

The natural resource conflicts happen when there is variation on how natural resources and related ecosystems should be managed, owned, allocated, used, and protected. However, most researches on resource conflicts among different users, could not see the primacy of looking into these conflicts from the angle of their socio-economic and political causes. This paper among other things sought the socio-economic and political triggers of renewable natural resources conflict in Southeastern parts of Nigeria. Data were collected from 300 crop farmers purposively selected from three States - Imo, Abia and Enugu, using structured questionnaire and oral interview. Percentage and mean were used to analyze the collected data. The renewable natural resources considered in the study area were water, crop land, forests, and fishers/marine resources among others. The socio-political drivers of renewable resources conflict includes demand induced scarcity (87.7%), environmental degradation (83.3%), migration of people (91.6%) and unclear rights (85.3%). The study found that to reduce the occurrence of natural resource conflicts, following measures should be in place; reducing vulnerability to resources scarcity (M=3.57), increased availability of scarce resources (M=3.60), discourage/stop degradation (M=2.50), good governance framework (M=3.36) and effective resource sharing agreement (M=3.56) among others. It is recommended to resolve the natural resource conflicts which can be achieved by equal distribution of resources, clear rights to resources and good land governance.

Keywords: Conflict, Farmer, Land, Natural resource, Renewable

Conflicts of interest: None

Supporting agencies: None

Received 17.02.2022; Revised 01.04.2022; Accepted 09.04.2022

Cite This Article: Chikaire, J.U., Atoma, C.N., & Ajaero, J.O. (2022). Socio-economic and Political Drivers of Renewable Natural Resource Conflicts among Crop Farmers in Southeast Nigeria. Journal of Sustainability and Environmental Management, 1(2), 46-51.

1. Introduction

Land and natural resources are getting more international

attention as a source of conflict. Changes in the character of violent

conflict, as well as with long-term demographic, economic, political and

environmental trends have practical implications for worldwide peace and

security challenges (UNO & EU, 2012b). Land and conflict are frequently

intertwined. Land and natural resource issues are frequently cited among the

underlying causes of conflict or as key contributing elements (UNEP, 2009; UNO

& EU, 2012b). Despite this reality, governments and the international

community have resisted creating systematic and successful ways to handle land

disputes and conflicts in the past. Land is thought to be politically sensitive

or technically complex to allow for effective resolution; but, as experience

has shown, this is a mistake. According to recent studies, wars over natural

resources are twice as likely to resurface within the first five years after

the conclusion of the conflict (UNEP, 2009).

Natural resource conflicts happen when parties differ on

how natural resources and related ecosystems should be managed, owned,

allocated, used, and protected. Conflict becomes an issue when the societal

procedures and institutions for managing and resolving conflict fail, allowing

violence to happen (UNO & EU, 2012a). Institutions that are weak, where

political systems that are unstable, can be dragged into cycles of conflict and

bloodshed. Scarcity of renewable resources, or concerns about their governance

and/or trans-boundary character, might drive, reinforce, or aggravate existing

stress and contribute for violence (UNO & EU, 2012a). Land and natural resources are getting more

international attention as a source of conflict.

Changes in the form of violent conflict, as well as

long-term demographic, economic, and environmental trends, provide enormous

practical challenges to global peace and security. Farmers and herders have

coexisted in West Africa for generations. This coexistence has not always been

easy, as it has been marked by both cooperation and strife (Tonah, 2002;

Shettima & Tar, 2008; Moritz, 2010). Reciprocity and exchange in many forms

have aided the establishment of interdependent connections between farmers and

herders (Seddon & Sumberg, 1997; Tonah, 2006; Moritz, 2010). In the past,

these symbiotic connections were crucial in preventing and resolving conflicts

between farmers and herders (Pelican & Dafinger, 2006; Moritz, 2010). In

many places of Sub-Saharan Africa, the frequency and spread of violent

farmer-herder clashes has increased.

The majority of violent farmer-herder conflicts in Nigeria,

as in many other parts of West Africa, involved the Fulani (or Fulbe) herders and settled farming populations. The

Fulani are West Africa's most powerful pastoralists (Abbass, 2014). In the

early 1920s and 1930s, Fulani nomadic herders began migrating into Nigeria,

Niger, Burkina Faso, Mali, and other African countries looking for pasture,

water, and improved economic opportunities (Tonah, 2000; Tonah, 2001). Fulani

herdsmen can now be found in practically all of Nigeria's agro-ecological

zones. As a result, there has been an increase in violent crime leading to

human deaths and displacement of people. Conflicts between farmers and Fulani

herders have become commonplace. In recent years, there has been an uptick in

the number of natural resource conflicts involving several resource users.

Farmer/herder disputes have become a typical occurrence

in West Africa throughout the years, as well as a common feature of their

economic life (Tonah, 2006; Turner, Ayantunde, & Patterson, 2011; Moritz,

2012). Farmer/herder disputes have erupted into widespread violence in many

parts of Sub-Saharan Africa, resulting in property devastation, human deaths,

and population displacement (Hussein, Sumberg & Seddon, 1999). The problem

of access to and use of land and water resources lies at the heart of

farmer/herder conflicts. Due to a variety of circumstances, land and water

resources are becoming scarcer or becoming scarcer, resulting in fierce

competition and violent conflict. Climate change is a significant element determining

resource availability for agricultural and pastoral output. According to Moritz

(2012), while climate change is occurring all around the world, the Sahel

region of Africa has been particularly turbulent in recent decades.

Climate change has resulted in a reduction in

environmental space as well as a rise in natural resource scarcity. As a

result, there is more rivalry and pressure on limited resources, as well as

tensions among user groups (Mwiturubani & van Wyk, 2010; Abbass, 2014;

Okoli & Atelhe, 2014). Pastoralists migrate from places marked by drought

and a lack of feed into new areas in response to climate change. In sub-Saharan

Africa, the southward migration of pastoral herds (Fulani herdsmen) into the

humid and sub-humid zones is among the factors cited for the widespread and

increasing farmer-herder conflicts (Tonah, 2006; Fabusoro & Oyegbami, 2009;

Moritz, 2010).

Resource shortage and violent conflict are also

attributed to population growth and the rise of agricultural productivity.

Rapid population growth raises the level of competition for limited resources

(Adebayo, 1997; Mwiturubani & van Wyk, 2010). As a result of population

growth, many pastoralists from the Sudan/Sahelian zone have moved south to

avoid conflicts, but this has resulted in the possibility for conflict with

farmers in new places (Moritz, 2012). Population growth, according to Williams,

Hiernaux, and Rivera (1999), has increased the need for food, resulting in the

extension of farming into previously uncultivated lands utilized for cattle

grazing. Commercial crop production results in encroachment on most of the

traditional cattle routes, leaving pastoralists with insufficient passage for

livestock to reach drinking points, causing conflicts (WANEP, 2010).

Expansion of agricultural output into historically

grazing regions and cattle pathways brings grazing livestock closer to cropped

fields, resulting in livestock induced crop damage (Turner et al., 2011). In

most parts of West Africa, livestock induced crop loss, whether on the field or

in farm storage, has been identified as the most common cause of farmer/herder

conflict (Tonah, 2002; Turner, Ayantunde, Patterson, & Patterson, 2007; Ofuoku

& Isife, 2009; Abubakari & Longi, 2014; Ofem & Inyang, 2014). Tonah

(2002) discovered that Fulani ranchers would generally allow cattle to roam the

entire plain, purportedly in search of grass and water, but with the goal of

prohibiting crops on the plain so that it could be used entirely by them.

Farmers and herders have been known to clash in the midst of abundant resources

and low animal and human population densities. This study was focused on the

socioeconomic and political triggers of farmer-header conflicts from the

perspectives of crop farmers in Southeast Nigeria. The specific objectives were

to a) identify renewable natural resources available in the study area; b)

ascertain socioeconomic and political drivers of renewable resource conflicts

in the study area and c) examine perceived strategies for preventing resource conflicts

in the area.

2. Materials and methods

This study was conducted in southeast agro-ecological zone of Nigeria. The zone is made up of five states - Abia, Anambra, Ebonyi, Enugu and Imo (Figure 1). The zone occupies a total land mass of about 10,952,400 hectares with a population of 35,381,729(NPC, 2006). The 2-stage sampling technique was adopted in the process of sample selection. The first stage was the purposive selection of three states from the Southeast agro ecological zone where cases of farmer-pastoralists conflicts have occurred and were reported (Abia, Enugu and Imo). The second stage involved the random selection of 300 crop farmers from the list of 3000 crop farmers in the three states. Both primary and secondary data sources were used. Mean was computed on a 4-point Likert type rating scale of strongly agree, agree, disagree and strongly disagree assigned weight of 4,3,2,1 to capture the perceived strategies for the prevention of natural resource conflicts. The values were added and divided by 4 to get the discriminating mean index value of 2.5. Any mean value equal to or above 2.5 was regarded as a major strategy for reducing conflicts, while values less than 2.5 were regarded as no strategy.

Figure 1: Map of Southeast Nigeria, showing the study locations - Imo, Abia and Enugu

3. Results and discussion

3.1. Renewable natural resources in the

study area

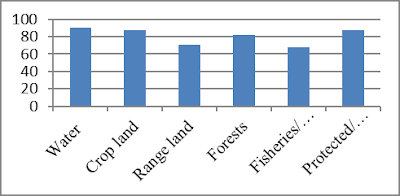

Figure 2 shows that plenty of renewable natural resources

exist in the study zones. Water (90.6%) was one of the major natural resource

in the study site. Pressure on limited available fresh water resources is

mounting driven by fast growing population, economic growth, pollution, and

loss of watersheds. Recently, climate change effects are likely to aggregate

water scarcity in almost every regions of the world. This has intensified

demand and complication for water and has affected water use twice due to

increasing rate of the population (UNESCO, 2009).

Crop land (87.6%) was another resource available in the study area in southeast Nigeria. Rangeland (70.6%), consisting of almost entire of the land, dry or too steeply sloping has supported the crop production. This type of land feature was seen around Enugu, and Uturu area of Abia State, Nigeria. Forests (81.6%) is a rich source of wood, timber, shrubs and so many other herbaceous plants succulent for animal feeds. Fisheries/means resource (68.3%) were received from rivers, oceans and streams unlawful, or unauthorized harvesting from the water.

Figure 2: Renewable resources in study area

3.2. Socio-economic and political

drivers of conflicts

Figure 3 shows

the socio-economic and political drivers of renewable natural resources

conflicts in the study zone. It includes demand-induced scarcity (87.7%). This

occurs when the demand for a specific renewable resources increase and cannot

be met by the existing supply. Water/cropland may be enough for users

initially, but once population increases, the consumption rates rises up and

availability of such resource becomes reduced. Another driver is supply-induced

scarcity (78.3%). This happens when environmental degradation, natural

variations or a breakdown in delivery infrastructure reduces the total supply

of resources. Once the supply of renewable natural resources is reduced,

options for pursuit of productive livelihood strategies are undermined, creating

competition between users. Structural scarcity is another driver (97%). This

occurs when different groups in the society face unequal resource access. As

they go to places with abundant resources, competition occurs giving rise to

violent conflicts. Migration (91.6%) and illegal exploitation (83.3%) are all

drivers of resources-conflicts. These occurs when pastoral livelihood groups

migrate across know land boundaries, over stepping traditional routes, they

quarrel with the crop farmers and eventually fight. Again, illegal activities

of criminal groups access boundary lines are sources of conflicts. When one

user group over steps their boundary to the detriment of another, conflicts are

bound to occur. These are called socio-economic dimensions of renewable natural

resources conflict. One other socioeconomic driver of renewable natural

resource conflicts is environmental degradation (93.3%). Here, due to high

population, the quantity and quality of natural resources have reduced and or

polluted. This impact seriously on the rural dwellers and is a precursor

promoting conflict/agitations.

The above findings agree with UN0 (2004) that Africa is at a crossroads. The continent’s share of the world population is increasing exponentially (from 8.9% in 1950 to 14% in 2005), and is projected to reach 21.3% in 2050. With a large majority of the population directly dependent on four key renewable resources that are especially crucial to food production – water, cropland, forests and fisheries – this growth in population does indeed present the largest and most complex of threats to human security. The availability of these key renewable resources determine the people’s well-being (Maphosa, 2012), and the scarcity of such resources under certain circumstances could lead to violent conflict. In effect, a reduction in the quantity and/or quality of a resource decreases the resource, while population growth divides the resource among people, and unequal resource distribution means that some groups get disproportionately larger allocations of the resource. Thus, increased environmental scarcity caused by one or more of the abovementioned processes may lead to several consequences, which in turn may generate armed and/or domestic conflict. Important intervening changes may include decreased economic activity and agricultural production, displacement of persons and compromised states.

The political

drivers of renewable natural resources conflict include unclear rights to land

and laws (85.3%), discriminatory policies (83%), unfair benefits/burdens

(82.6%), lack of public participation (85%) unequal/inflexible use (87%),

unclear overlapping or poor enforcement of resources rights and laws, bring

problems to land-users. Land use and right are regulated under various

statutory, customary and informal rules which are not too clear and brings

confusions. These rules bring disagreements and uncertainty over resources

rights among users. Again, there are discriminatory policies, rights and laws

that marginalize certain resource-user groups. When one resources-user group

controls access to renewable natural resources to the detriment of others,

other communities dependent on that particular natural resource will suffer. When

benefits are unequally distributed, ill-feelings and agitations will start.

Lack of public participation and transparency in decision making is always a

problem due to top-down approach. When communities and stakeholders are poorly

engaged or excluded from the natural resources decision making, they are likely

to oppose any related decisions and outcomes.

That is why natural resource conflicts have been defined as “a social or political conflict where natural resources contribute to the onset, aggravation, or sustaining of the conflict, due to disagreements or competition over the access to and management of natural resources, and the unequal burdens and benefits, profits, or power generated thereof” (Schellens & Diemer, 2020). Other terms used for natural resource conflicts, with slightly different meanings, are environmental conflict, socio-environmental conflict, ecological distribution conflict, and climate conflict. Environmental conflicts distinguish themselves as being induced by human-caused environmental degradation, and thus always focus around renewable resources (Libiszewski, 1992). Socio-environmental conflicts and ecological distribution conflicts are synonyms, sometimes also seen as synonymous to environmental conflict (Martinez-Alier & O’Connor, 1996; Temper et al., 2018). They are described as “social conflicts born from the unfair access to natural resources and the unjust burdens of pollution” (Martinez-Alier and O’Connor, 1996), placing their main focus on inequality and access. Climate-conflicts arise from a change in availability or access to natural resources due to climate change (Mazo, 2010; Scheffran et al., 2012) and can thus be considered a sub-type of natural resource conflicts. The unequal distribution of burdens and benefits, profits and power generated from resource exploitation is the direct socio-economic and political context that creates resource grievances (Must, 2016; Lessmann & Steinkraus, 2019). Without strong agreements on the access to, and the management of, natural resources, disputes and competition can develop into violent conflicts (Must 2016; Olsson and Gooch, 2019b).

3.3. Strategies for prevention of

renewable natural resource conflicts

Table 1 shows the various perceived conflict prevention approaches to avoid, minimize, and resolve conflicts. These are useful where natural resources are a direct sources of conflicts. The approaches include supporting sustainable livelihoods (M = 3.4), reducing vulnerability to resource scarcity (M = 3.57), increase availability of scarce resource (M = 3.60), discourage/stop degradation (M = 2.90), framework for good resource governance (M = 3.28), civil society as part of resource governance (M = 3.36), proper trans-boundary information (M = 3.80), and effective resource-sharing agreements (M = 3.56). The above agrees with UNO and EU (2012), understanding livelihood methods in a particular location, especially if livelihoods compete for the same limited natural resources, is critical to developing conflict avoidance or management techniques (Chikaire, Ajaero, & Atoma, 2022). The threats to minority groups and indigenous peoples, in particular, must be assessed. Addressing inequitable access, reducing corruption and improving transparency, preventing environmental degradation, establishing and enforcing rights and rules over natural resource use, fostering parliamentary oversight, enhancing public participation in the design and acceptance of such rules, and ensuring the transparent identification of any poachers are all examples of ways to improve resource governance.

4. Conclusion

Conflicts over

renewable resources generally arise as who should have access to and control

over the natural resources (cropland, water, pasture, forests and sacred

areas), and who can influence decisions regarding their allocation, sharing of

benefits, management and rate of use. It is critical to note that disputes and

grievances over natural resources are rarely, if ever, the sole cause of

violent conflict. The drivers of violence are most often multi-faceted (unclear

rights, lack of legislation, uneven distribution among others). However,

disputes and grievances over natural resources can contribute to violent

conflict when they overlap with other factors, such as ethnic polarization,

high levels of inequity, poverty, injustice and poor governance. For resolving

the natural resource conflicts, there should be equal distribution of

resources, clear rights to resources and good land governance measures.

References

Abubakari, A., & Longi,

F. Y. T. (2014). Pastoralism and violence in northern Ghana: Socialization and

professional requirement. International

Journal of Research in Social Sciences, 4(5), 102-111.

Adebayo, A. G. (1997).

Contemporary dimensions of migration among historically migrant Nigerians. Journal of Asian and African Studies,

32(1-2), 93-109. https://doi.org/10.1177/002190969703200108

Chikaire, J., Ajaero, J.,

& Atoma, C. (2022). Socio-economic effects of Covid-19 pandemic on rural

farm families’ well-being and food systems in Imo State, Nigeria. Journal of Sustainability and Environmental

Management, 1(1), 18–21.

Fabusoro, E., &

Oyegbami, A. (2009). Key issues in livelihoods security of migrant Fulani

pastoralists: empirical evidence from Southwest Nigeria. Journal of Humanities, Social Sciences and Creative Arts, 4(2),

1-20.

Hussein, K., Sumberg, J.,

& Seddon, D. (1999). Increasing violent conflict between herders and

farmers in Africa: claims and evidence. Development

Policy Review, 17(4), 397-418. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-7679.00094

Libiszewski, S. (1992). What is an environmental conflict? In

ENCOP Occasional Papers, 15. Berne/Zürich, Swiss.

https://www.files.ethz.ch/isn/236/doc_238_290_en.pdf4

Lessmann, C., & Arne S.

(2019). The geography of natural resources, ethnic inequality and civil

conflicts. European Journal of Political

Economy, 59, 33–51

Maphosa, S.B. (2012). Natural resources and conflict: Unlocking

the economic dimension of peace-building in Africa. Africa Institute of

South Africa.

Martinez-Alier, J., &

Martin O. (1996). Ecological and economic distribution conflicts. Practical Applications of Ecological

Economics, 153–83.

Mazo, J. (2010). Climate

conflict: How global warming threatens security and what to do about it. The Adelphi Papers, 49 (409), 1–168.

https://doi.org/10.1080/19445571003755405.ARNSTITUTE

Moritz, M. (2010).

Understanding herder-farmer conflicts in West Africa: Outline of a processual

approach. Human Organization, 69(2),

138-148. https://doi.org/10.17730/humo.69.2.aq85k02453w83363

Moritz, M. (2012). Farmer-herder conflicts in sub-Saharan

Africa. Retrieved from http://www.eoearth.org/view/article/152734

Must, E. (2016). When and how does inequality cause

conflict?: Group dynamics, perceptions and natural resources. London School

of Economics and Political Science (University of London).

http://ethos.bl.uk/OrderDetails.do?uin=uk.bl.ethos.702961

Mwiturubani, D. A., &

Van Wyk, J. A. (2010). Climate change and

natural resources conflicts in Africa. Institute for Security Studies.

Retrieved from http://uir.unisa.ac.za/bitstream/handle/10500/13312/Climate%20change%202010.pdf?sequence=1

Ofem, O. O., & Inyang, B. (2014). Livelihood and conflict dimension among crop farmers and Fulani herdsmen in Yakurr region of Cross River State. Mediterranean Journal of Social Sciences, 5(8), 512-519.

Ofuoku, A. U., & Isife,

B. I. (2009). Causes, effects and resolution of farmers-nomadic cattle herders

conflict in Delta state Nigeria. International

Journal of Sociology and Anthropology, 1(2), 047-054.

Okoli, A. C., & Atelhe,

A. G. (2014). Nomads against natives: A political ecology of herder/farmer

conflicts in Nasarawa state, Nigeria. American

International Journal of Contemporary Research, 4(2), 76-88.

Olsson, E., Gunilla, A.,

& Pernille G. (2019). The sustainability

paradox and the conflicts on the use of natural resources.

https://doi.org/10.4324/9781351268646.CH 2012

Pelican, M., & Dafinger, A. (2006).

Sharing or dividing the land?: Land rights and herder-farmer relations in a

comparative perspective. Canadian Journal

of African Studies, 40(1), 127-151.

Seddon, D., & Sumberg,

J. (1997). Conflict between farmers and

herders in Africa: An analysis. Retrieved from https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/media/57a08d5140f0b649740017b8/R6618a.pdf

Shettima, A.G., & Tar,

U.A. (2008). Farmer-pastoralist conflict in West Africa: Exploring the causes

and consequences. Information, Society

and Justice Journal, 1(2), 163-184.

Scheffran, J., Michael, B.,

Jasmin, K., Michael, L., & Janpeter, S. (2012). Disentangling the climate

conflict nexus: Empirical and theoretical assessment of vulnerabilities and pathways.

Review of European Studies, 4 (5).

https://doi.org/10.5539/res.v4n5p1

Schellens, Marie K., and

Arnaud, D. (2020). Natural resource

conflicts: Definition and three frameworks to aid analysis. Springer

Nature.

Tonah, S. (2000). State

policies, local prejudices and cattle rustling along the Ghana-Burkina Faso

border. Africa, 70(4), 551-567.

https://doi.org/10.3366/afr.2000.70.4.551

Tonah, S. (2001). Fulani pastoral migration, sedentary farmers

and conflict in the middle belt of Ghana. Paper presented at the National

Conference on Livelihood and Migration, ISSER, University of Ghana, Legon.

Tonah, S. (2002). Fulani

pastoralists, indigenous farmers and the contest for land in Northern Ghana. Africa Spectrum, 37(1), 43-59.

Tonah, S. (2003). Conflicts and Consensus between migrant

Fulani herdsmen and Mamprusi farmers in northern Ghana.

Tonah, S. (2006).

Migrations and farmer-herder conflicts in Ghana's Volta Basin. Canadian Journal of African Studies,

40(1), 152-178.

Turner, M., Ayantunde, A.A.,

Patterson, E.D., & Patterson, K.P. (2007). Conflict management for improved livestock productivity and sustainable

natural resource use in Niger. Retrieved from

https://cgspace.cgiar.org/bitstream/handle/10568/1304/ILRIProjectDoc.pdf?sequence=3&isAllowed=y

Turner, M. D., Ayantunde,

A. A., Patterson, K. P., & Patterson, E.D. (2011). Livelihood transitions

and the changing nature of farmer–herder conflict in Sahelian West Africa. The Journal of Development Studies,

47(2), 183-206. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220381003599352.

UNESCO (2009). Water in a changing world. Paris.

UNEP (2009). From

conflict to peacebuilding: The role of natural resources and the environment.

Nairobi.

UNO and EU (2012a). Renewable resources and conflicts. New

York

UNO and EU (2012b). Land and conflicts. New York

UNO (2004). Department of economic affairs: Population

Division. New York

WANEP (2010). Concept paper on agriculture and pastoralist

conflicts in West Africa Sahel. Retrieved from http://www.wanep.org/wanep/attachments/article/158/cp_agric_pastoralist_aug2010.pdf

Williams, T. O., Hiernaux, P., & Fernández-Rivera, S. (1999). Crop-livestock systems in sub-Saharan Africa: Determinants and intensification pathways. Washington DC.

|

|

©

The Author(s)

2022. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and

conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license. |